A play with Sudowrite

Last time, I wrote about Creativity Boosting AI, with GitHub Copilot and Sudowrite as specific examples. These tools don’t replace humans, but rather pair with you to help you create.

When I wrote that, I didn’t have access to Sudowrite. Since then, I’ve joined the beta and had a chance to play with it. I’ll share a bit of that experience here in a moment.

Before that, I just wanted to mention that I have started the edits on my still unnamed publishing-for-programmers book. I don’t have a timeline set for it yet, because I’ve got a busy August, making it unpredictable how quickly I will get through the process.

Sudowrite

Sudowrite is intended to be a partner in fiction writing. It’s based on GPT-3, but “raw GPT-3” is hard to use directly and Sudowrite tweaks the input to try to get useful output. By way of example, I decided to work with some text in the first episode of The Dragon of DC, my new Kindle Vella serial. (The episode is free, so you can take a look if you want to see more of the input that Sudowrite was working from … I’ve included enough context here, however, so you don’t need to do that.)

Sudowrite has a describe feature. Select some text and hit the button, and out comes multiple descriptions for each of the senses. I wanted to see what kind of description it might produce for Senator Anderson’s office, so I selected “her office in the Russell Senate Office Building” (which doesn’t actually appear in the original text of episode 1, because I did describe her office).

The first thing I’ll note is GPT-3 is going to give you nonsense. Seriously, like every time. If you want to write alongside an AI, you’re going to need to curate its output for something useful. I think this is fine, because to me the whole concept is that it gives you ideas you would not otherwise have thought of.

Here’s an example office description for sight:

A onetime secretary's desk, twice as big as the average desk, filled with ornaments and gilt paperweights. Senator Margaret Anderson’s desk had three levels of filing cabinets nestled in the corners, each one filled with folders of papers that sat in perfect stacks on each corner of the desk. The folders were either white or pale yellow, and most of them had to be at least five inches thick.

First thing to note is that it pulled Senator Anderson from the first part of the sentence and not the selected text. The rest of the description is interesting. Stacks of filing cabinets filled with five-inch-thick folders? Paperweights and ornaments around the desk? This is an interesting desk and not what I would have pictured myself. Also probably not a likely desk for a US Senator. Especially, when we look at the remainder of the paragraph:

Ten-year-old Margaret had fallen in love with the look of some of the papers. They looked like what she imagined the archives of ancient Egypt to look like.

Oops! Somehow our Senator is only 10. Still, I can imagine having fun with a character possessing such a desk.

The next sight description was interesting:

Light from the Capitol skittered across the windows.

The text around this selection didn’t say anything about the Capitol! Something about Margaret being a Senator or the Russell Senate Office Building was enough for GPT-3 to figure out that she’s near the Capitol.

Other senses

Under smell, we had this one:

The scent of a hundred years of Washington, DC.

Nice. For sound:

The subtle ping of the printers, the scratch of a woman's shoes on marble, the rumble of a man's whisper.

The sense of taste often leads to odd descriptions, including this one which may be thinking of “taste” in the sense of style and not what your tongue senses:

Margaret's office was just a large room with a desk in it, some chairs, and a credenza. The ceiling was high, and the walls were plastered white.

The “metaphorical” descriptions included:

There were too many desks.

And this one, which is actually kind of intriguiging:

Glass built-in bookshelves flanked both sides of her walnut desk. The books were so old, the white of their pages had yellowed to a dusty gray, and their spines, deeply bowed, were cracked at the bases. Spread across the desktop was a large paper map, its borders thick with red lines marking boundaries between countries and states, its middle covered with small white circles indicating cities and towns.

Had I been stuck, I could imagine such a prompt helping me get unstuck.

Wormhole

The idea behind Sudowrite’s Wormhole is to look into directions your story could take with “neutral”, “ominous”, “extraordinary”, and “funny” variations. Again, this is the nice thing with Sudowrite: it’s not just raw GPT-3. I put my cursor after the highlighted paragraph in this image:

The first Wormhole result invented a character named George Dillin:

George Dillin was lost, but he didn't care. He was in a part of the building that he figured few people ever use, let alone visitors like himself. He was reminded of an old tv show, Columbo, where a murder victim's house was musty and dusty, full of books, antiques, and other odds and ends, and a well-worn trail of rat droppings told the viewer who scampered around. Over the years, the government had learned most of the tricks of the old police dramas, forcing criminals to get more sophisticated. The downside was that they often resorted to plain mischief or simple pranks, as the case may be, to delay or prevent detection.

Part of that strategy was to force investigators to expend time and effort tracking down cases that didn't really exist. So George was enjoying himself, especially after he was sure that the people who had gone into the room behind him wouldn't come back immediately. Sprint

Yes, it ended with the word “Sprint”. This direction wasn’t useful for my story, but could have been.

I’ll note that my story has a character nicknamed Three. Sudowrite was totally cool with that.

Three walked back into the main lobby and left the building, only to find hundreds of protestors rallying right outside. He turned around and headed back to Senator Anderson's office. A few reporters spotted him and managed to get the news out that he was there despite his best efforts to be inconspicuous. They wanted to talk, and Three was polite but frustrated.

This episode is actually called “The Protest” and does feature protestors. The generated text above was followed by a couple paragraphs about an announcement of an announcement, which was a bit odd.

Wormhole being funny

AI isn’t necessarily known for being able to tell a joke, so I was curious what happens with the “funny” filter on the Wormhole. It looks like it takes your text and adds “And then something funny happened:” to prompt GPT-3. This was kind of funny:

just as he'd turned back toward the exit, he saw someone step up to the security guard's counter. The man said two words, "Robert Allen Anderson," and suddenly a smile crept onto the guard's face.

Apparently, it’s not very good at counting words. In general, though, these Wormhole results were no funnier in this case. However, as with the neutral case, the generated text did include different directions that could provoke further ideas.

Going for something extraordinary gave me this:

the lights in the hallway went out.

"What in the name of the Flying Saucer—" Margaret began, then a door to the right of hers jerked open, and three men and a woman in red, white, and blue masks leapt through it.

Perhaps it was the lingering adrenaline, but Margaret didn't feel frightened. Perhaps it was the fact that one of the men was about five feet tall and covered in hair on the chest and arms. The strangest thing she felt about him was that he wasn't wearing jeans. He was wearing tight black unitards.

The thing she focused on was that he was the one holding the gun.

What in the name of the Flying Saucer, indeed!

And there’s more

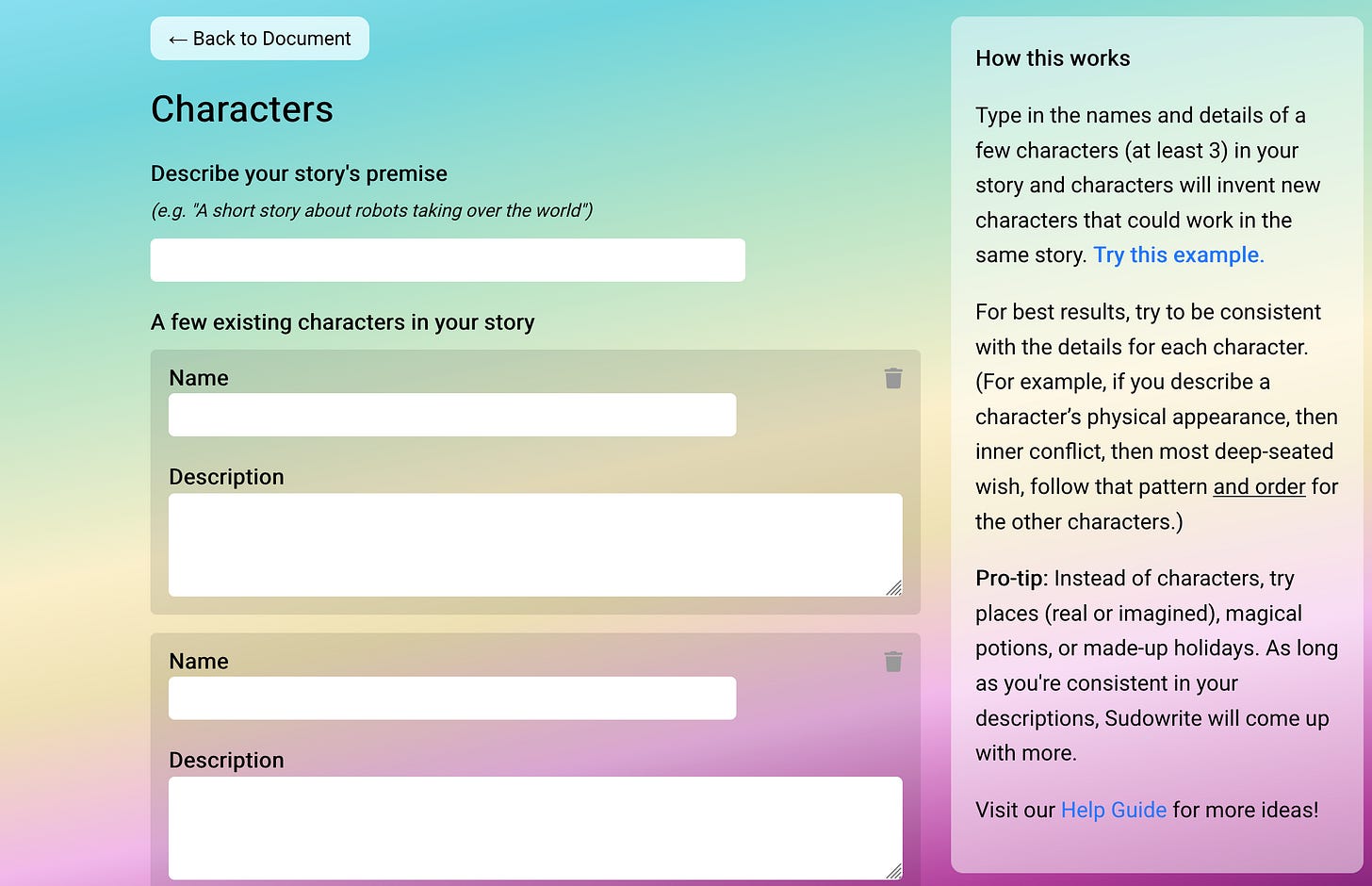

Sudowrite also includes “Twist”, “Characters”, and “Poem” generators. These generators don’t work based on your main document, but rather by tailored descriptions you give. Here’s what the Characters input is like:

I don’t want to go on too long with this message, but I did want to give you a sense of what kind of text Sudowrite will give you with a couple of inputs.

My thoughts

Joanna Penn interviewed Sudowrite creator Amit Gupta and Amit said that it’s not really intended for you to just take the text it generates and drop it in your book. I think the samples above back that up. That said, I did think the output was useful and really could give me ideas for descriptions and story elements.

Is it $20 per month useful? Potentially. If I’m doing a lot of writing one month and I’m looking to make fast progress (say National Novel Writing Month), maybe Sudowrite will keep me from getting stuck. Or maybe I’d spend more time curating the output? It’s hard to say, but for my current writing pace, I don’t think I’d spend $240 for a whole year of service, but can absolutely imagine subscribing for some months of the year.

Given that many of the readers of this list are more interested non-fiction topics than fiction, I don’t personally see this sort of technology being useful for non-fiction any time soon. Formulaic non-fiction, like articles based on earnings results or sporting events, has been generated by AI systems for some time, but most non-fiction doesn’t look like that.

I do see the possibility that sophisticated models like GPT-3 will help non-fiction writers with research and connecting more dots, but likely with a lot of human curation and verification. It’s still early days and this technology is improving rapidly, so I remain eager to see what comes next.